Most voters assume the way we vote is fair. When unexpected outcomes occur, such as a third party influencing an election result or a large fraction of voters being denied representation, they often accept it as an unchangeable aspect of the system. Many people feel powerless, viewing voting systems as fixed structures. This primer aims to highlight these issues and show that we can improve how we select our leaders and make collective decisions.

Background

This primer was created for residents of Los Altos, CA, but should be valuable for any jurisdiction facing action under the California Voting Rights Act (CVRA). It will also interest anyone looking to understand the recent trend in the US toward fairer elections through ranked choice voting. The primer aims to provide readers with a solid intuition of ranked choice voting and illustrate through examples how it addresses issues inherent in some traditional voting systems.

The CVRA was enacted in 2001 to ensure fair representation for minority groups in local elections. It aims to eliminate election systems that may dilute the voting power of minority populations, often resulting in underrepresentation. The CVRA allows minority groups to challenge these systems in court. If a court finds that an at-large system impairs minority voting rights, the local government must implement district elections where each district elects its own representative.

On April 14, 2024, the City of Los Altos faced a lawsuit threat under the CVRA, alleging that the voting power of Asian Americans was being diluted. The city quickly began transitioning to district-based voting, and will likely divide its 30,000 residents into districts each represented by a single council member, with a possibility of a city-wide elected mayor. This move has sparked significant public outcry and concerns from most city council members. Given the few candidates who typically run for office, many district elections may end up with zero or only one candidate, leading to uncompetitive races. Additionally, this setup may foster divisions within the town as districts compete for resources.

The purpose of this document is to educate individuals about the various incentives and motivations behind current and alternative voting methods. Voting systems can significantly impact election outcomes, representation, and fairness. By understanding these methods, individuals can better grasp how each system incentivizes certain behaviors among voters and candidates. This knowledge is crucial for making informed decisions about advocating for or participating in elections, ensuring that the method used aligns with the values of fairness, representation, and inclusivity.

In the following, example elections are simplified and do not involve political parties or controversial issues. For simplicity and clarity, they use a population of 100 voters, divided into blue, orange, green, and purple communities. Each community has preferred candidates, labeled "Blue 1" for the top choice and "Blue 2" for the second choice, and so on. While real communities don't vote as a single block and may support candidates in different orders or from other communities, these simplifications help illustrate the concepts clearly.

Current Elections

When a board or council elects multiple open seats, each voter gets as many votes as there are open seats. This approach is so common that it seems like the default, and few question its fairness. However, this method can be unfair and effectively suppress the voices of significant portions of the population, even those representing nearly half of the voters.

The next figure shows a three-seat election where the blue and orange communities each have three preferred candidates. If one community has a slim 51% majority and votes as a bloc for their candidates, they can win all the seats. This leaves the other community's perspective completely unrepresented on the council, potentially leading to frustration and division. Additionally, if the minority viewpoint is actually correct, there is no way for them to be heard or influence the council's decisions. Thus, we can see the merit of a CVRA lawsuit filed against jurisdictions that vote with this method.

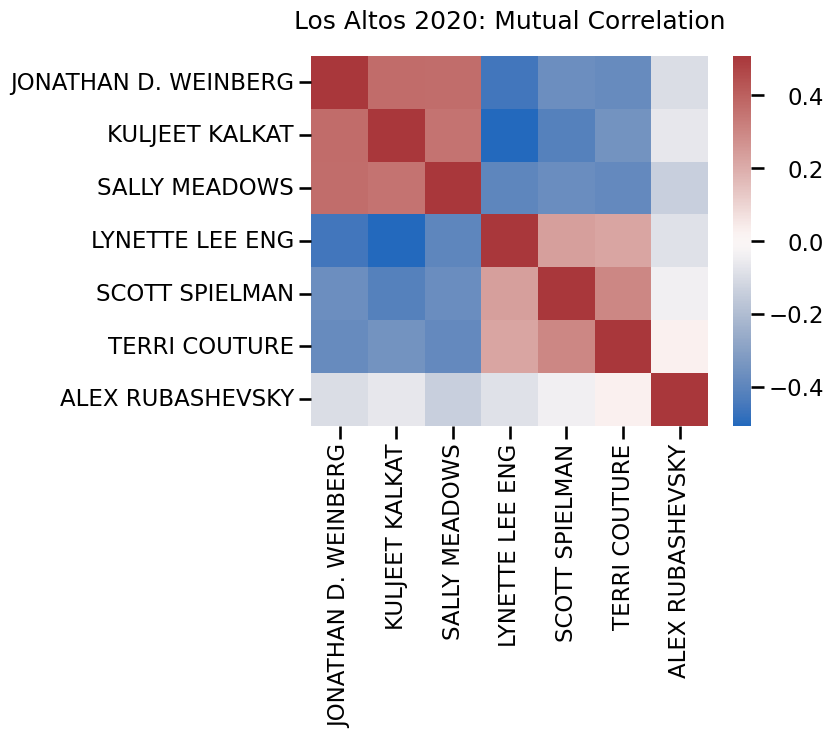

Even in a small town such as Los Altos, divisions into voting blocks like demonstrated above do occur. Data from ballots cast in the last 2020 Los Altos City Council election reveal clear voting patterns and voter blocks. In that election there were seven candidates, and two sets of three candidates were more likely to occur together on a ballot. The following figure highlights the presence of distinct voter blocks, demonstrating how certain groups of voters consistently support specific sets of candidates. This pattern underscores the need to consider more equitable voting systems that ensure fair representation for all communities. (More data breakdowns about this and other multi-seat elections.)

A Solution: Proportional Ranked Choice Voting

To understand how to avoid the problem of unfair representation, we first need to identify its cause: each voter is given multiple votes, one for each open seat. It is almost as if each seat a separate mini-election, allowing the majority group to win every seat. [This is not quite correct, but gives some intuition as to where the unfairness is coming from.] To create a fairer system, each voter should have a single vote and aim for the council to reflect the population.

Proportional ranked choice voting (PRCV) solves this problem by ensuring each voter gets just one vote, and the winners are chosen proportionally. In a single-seat election, a candidate must get more than 50% of the vote to win. In a two-seat election, the threshold is 33.3%, and for a three-seat election, it's 25%. [In math-speak, this is 100% ÷ (#seats + 1).] The following sections will demonstrate how this works, starting with what a ballot could look like.

Ranked Choice Ballot

Ranked Choice Ballots are a simple change to the current ballot which allow much more expression about candidates. Just like when you go the store to pick up cookies, you can have multiple favorites — if your top choice is out of stock, you can always pick up your second choice. The following is a mock ballot showing one way that ranked choice ballots could be designed. It is clear and intuitive - you fill in one bubble in each row and column to indicate the order you prefer candidates. And it is OK to not rank all the candidates — any candidates you do not rank are never given your vote.

The changes for the voter are minimal, so now let’s dig into mechanics of vote counting. We’ll break it into two pieces: the “proportional” piece, and the “ranking” piece.

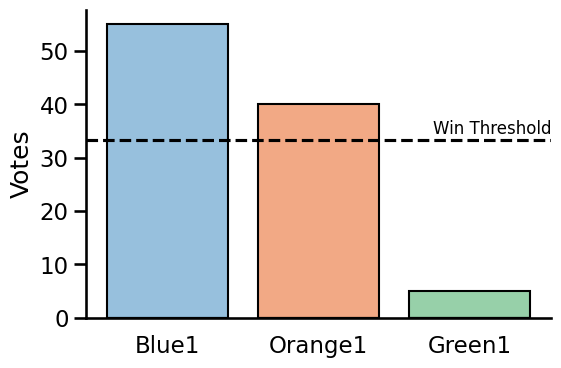

First: Understanding Proportionality

Let's look at a scenario where ranking does not yet come into play to see how the proportional aspect works. All that will matter is every voter's first choice. In the following two-seat election, the blue and orange communities each have significant support, while the green community is much smaller. The blue and orange candidates both surpass the 33.3% threshold and each win a seat. The green community, representing a smaller fraction of voters, misses the threshold and does not gain a seat. Because the votes sum to 100, only only two candidates can surpass the 33.3% threshold.

This example illustrates how ranked choice voting can lead to wins for candidates with strong community support, while candidates with less support are not elected. Note that the outcome is different than the situation where every voter was given two votes. A second vote would give the Blue community (with over 50% support) the ability to win two seats.

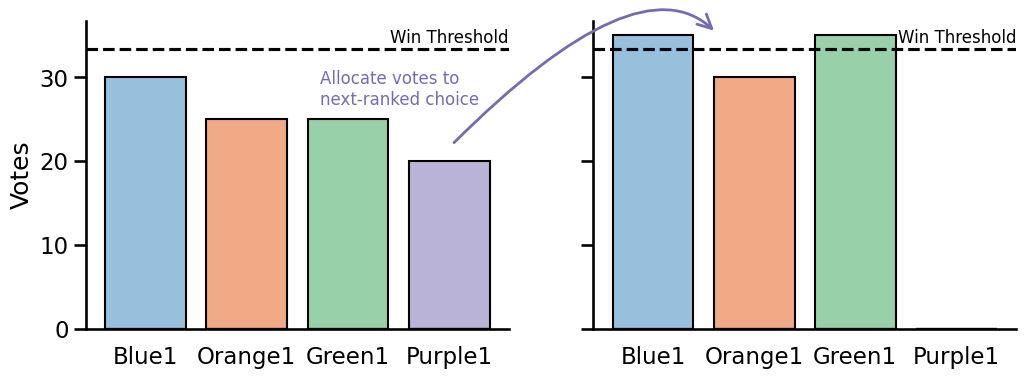

Next: Understanding Ranking

Now, consider a scenario where no communities initially meet the win threshold. We will see how the ranking comes into play. In this example, we have 4 candidates representing 4 communities. After using everyone's top choice, no candidates cross the threshold. This can happen if there are many candidates and none are clear favorites.

In a PRCV election, the candidate who has the fewest votes is eliminated. In the example below, this is the purple candidate. All votes are now re-tallied using the highest ranked candidate still in the election. This process is similar to holding a primary election followed by a general election, except another (expensive!) election is not needed. But there is no need to revote: the rankings allows us to determine each voters' top choice among the remaining candidates! Ranked choice voting ensures that all voters still have a say in the outcome, even if their top choice doesn't initially win, leading to a more representative and cost-effective election process.

Example: Winning Multiple Seats Requires More Support

Now let's explore a case where a single community is large enough to secure both seats in a two-seat election. Imagine the blue community is unified and strongly supports two candidates. Assume they all vote with Blue1 ranked first, and Blue2 ranked second. Initially, the Blue1 candidate receives enough votes to greatly exceed the 33.3% threshold required to win a seat. Given the large level of support, it would be unfair to the Blue community to allow the next highest candidate, which could have very low support, to win a seat.

To maintain fair representation, a portion of each Blue voter's support for that candidate is transferred to their next choice. It’s as if the Blue community split their voting power among their two candidates - but they could just vote their preferences and didn’t need to coordinate.

This redistribution accurately reflects the voting power of the blue community. This method shows that proportional ranked choice voting ensures balanced representation, requiring a community to have more than 66.67% support to elect both candidates.

Proportional Voting in Los Altos Should Avoid Action Under CVRA

Proportional Ranked Choice Voting (PRCV) allows a city to maintain at-large districts while ensuring the council reflects the diverse voting population, addressing concerns raised under the California Voting Rights Act (CVRA). Although case law is still evolving, the city of Albany successfully adopted PRCV to avoid CVRA action, resulting in the historic election of an Asian American and a Latino to their council. [More details about Albany can be found in Appendix.] This example suggests that PRCV can effectively counter legal challenges and promote fair representation.

In Los Altos, a lawsuit threatened by Kevin Shenkman alleges that Asian American votes are diluted, preventing them from electing candidates proportional to their population. As demonstrated in the earlier example without PRCV, non-majority communities can indeed be denied representation. Whether this occurs in Los Altos remains uncertain, but even the partial truth of this claim undermines democratic principles.

Examples: Two-Seat and Three-Seat Elections with a 37% Minority Community

With an Asian American community comprising approximately 37% of Los Altos, PRCV can enable them to elect two council members (assuming, for the moment, that they actually do vote as a block). The following examples explore the worst case scenario, where a minority community is up against a majority community that is also voting cohesively.

In the two-seat election, a split of 63% vs. 37% between two communities would see the minority group secure one seat, as they exceed the 33.3% threshold. Similarly, in a three-seat election, the minority community, being above the 25% threshold, could win one seat, while the majority community would win two, reflecting the proportional size of each group. These examples demonstrate that even in a worse-case scenario, a minority group representing at least 33% voting as a bloc can still achieve two seats on a five-seat city council.

Proportional Voting in Los Altos

A city can implement proportional ranked choice voting to ensure fair representation and reflect the diversity of its population. To do this, the city council has two options.

Charter

The first option is to draft and approve a charter that includes provisions for PRCV, as it is not currently part of California general law. This charter would then be put to a vote in a citywide election, allowing residents to decide whether to adopt the new voting system.

General law cities in California follow state laws for governance, while charter cities have more flexibility to create their own rules through a locally crafted charter. Since PRCV is not included in California's general laws, Los Altos would need to become a charter city to implement this voting method. The proposed charter would specifically adopt ranked choice voting, ensuring a more representative electoral process for the community.

In the case of Los Altos, see below for the timeline for getting a charter after the CVRA threat letter in April 2024. The city council needed to draft the charter, hold public consultations, and secure approval well in advance of the November ballot. The council had to start the process within 45 days of receiving the letter. Unfortunately, the city council's progress on this issue did not meet these deadlines.

April 14, 2024: Letter from Kevin Shenkman alleging CVRA violation

May 29, 2024: Notice of first public hearing is advertised [deadline]

June 19, 2024: First public hearing [deadline]

July 19, 2024: Second public hearing [deadline]

August 9, 2024: Adoption of resolution calling for election [deadline]

November 5, 2024: Election Day

A new charter can only be proposed in even-year elections, so the next opportunity for a charter in Los Altos will be the 2026 election.

District Bill

A state legislator can craft a bill tailored to one of their specific jurisdictions by focusing on the unique needs, challenges, or opportunities within that area. The Los Altos city council could ask our representatives to craft a bill allowing us to use ranked-choice voting as an alternative. Note that this bill is permissive, and not a mandate — it simply allows RCV as a choice.

An example of such a bill is AB-1227, signed into law in 2023, which allows the county of Santa Clara the ability to use ranked-choice voting.

Districts - The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly

The go-to remedy to avoid litigation under the CVRA is to divide a city into voting districts, where each district is represented by a single city council member. The division must take into account communities of interest, as expressed by the citizens and council, but does not actually have to mitigate the alleged issue. It's simply that the CVRA allows district-based elections a safe-harbor from potential litigation.

When a city opts to divide itself into districts for city council elections, it fundamentally alters the dynamics of local governance and representation. One key upside is that candidates no longer need to canvas the entire city, focusing instead on their specific district. While this makes it easier for individuals to run for office—since they can concentrate their efforts and resources on a smaller area—it also means that residents have less influence on the overall makeup of the council. In a district-based system, a candidate doesn’t need to be broadly popular city-wide; they only need to win over a smaller, potentially more homogeneous segment of the population. This can lead to situations where, due to vote splitting among multiple candidates, a person could win with a relatively low percentage of the vote, raising concerns about the legitimacy and representativeness of such elections.

Uncompetitive elections are another potential downside of district-based systems. The table below (raw data) shows that in nearby cities, there is a large decline in electoral competition after moving to district-based elections, with many seats going uncontested.

In particular, this leads to many citizens rarely having a choice in their local representation. As an example, in 2024, a resident of Menlo Park district #3 has a single candidate running to represent them. Those residents last voted for representation in 2020, and will not have the chance again until 2028.

Moreover, dividing a city into districts can create a new challenge: competition for resources between those districts. While this may not happen immediately, over time, council members might prioritize the needs of their own districts over the needs of the city as a whole. This could lead to uneven development, with certain areas receiving more attention and resources than others, potentially deepening divisions within the community.

In conclusion, while district-based elections can make it easier for individuals to run for office, they also present significant downsides, including reduced voter influence, decreased electoral competitiveness, and the potential for resource competition between districts. The choice between four or five districts, and the corresponding mayoral system, adds another layer of complexity, requiring careful consideration of the long-term impacts on representation and governance in the city.

Appendix

FAQ

What if a ballot doesn't rank all candidates and the ballot's candidates are eliminated?

The ballot is no longer considered. This is similar to when a voter votes in a primary race but chooses not to vote in that race's general election. In both cases, the voter has indicated they have no preference among the remaining candidates. It is important to note that the thresholds for a candidate to be elected are determined based on the number of ballots still under consideration (also similar to the primary and general election scenario).

District voting ensures that people living in a particular area can choose representatives who will advocate for issues that directly impact their community. Is this lost with Proportional Ranked Choice Voting?

No! PRCV offers a more flexible approach to representation than traditional district-based systems. While districts typically prioritize geographic boundaries, PRCV allows voters to group based on various shared interests or concerns. This could be anything from geography (just like districts!) to occupation or socioeconomic status to race or political ideology. As issues evolve over time, PRCV adapts, ensuring that diverse viewpoints are represented in government.

Albany, CA Timeline

The city of Albany recently avoided a CVRA action brought by Kevin Shenkman by pro-actively adopting Proportional Ranked Choice Voting. The following is a timeline of the events that unfolded in that process.

Jun 01, 2020: The City Council voted to put a PRCV ordinance on the November 2020 ballot. (Albany's charter allows the council to set the election method by ordinance.)

Jul 20, 2020: The City of Albany receives a CVRA notice letter from Kevin Shenkman on behalf of the Southwest Voter Registration Education Project (SVREP), presumably sent because a City Council member asked him to. It specifies both Latinos and Asians as the protected groups.

During 2020: SVREP agrees to wait until after the election to see if Measure BB passes before insisting that Albany implement district elections.

Nov 03, 2020: Measure BB passes, instituting PRCV for Albany beginning with the 2022 election.

During 2021 and beginning of 2022: SVREP, the City of Albany, and VCA enter a complex three-way negotiation process to figure out what to do to resolve the CVRA situation. They work out a pre-litigation settlement where SVREP will simultaneously file a CVRA lawsuit against Albany and a stipulated judgement that allows Albany to implement PRCV and continue to use PRCV as long as the first two elections under PRCV prove to be an adequate remedy to the CVRA allegations, to be determined by a "meet and confer" session within 90 days of each election. (Burden of proof on SVREP to prove that it isn't.) The agreement includes Albany paying SVREP $95K to reimburse Shenkman for his work up to the point of entering the stipulated judgement, and $10K after each of the first two PRCV elections to cover the costs of the "meet and confer" sessions.

Mar 14, 2022: VCA's attorney signs the pre-litigation settlement.

Mar 16, 2022: SVREP's President signs the pre-litigation settlement.

Mar 17, 2022: SVREP's attorney (Shenkman) signs the pre-litigation settlement.

May 09, 2022: The City of Albany (City Manager and City Attorney) finally signs the pre-litigation settlement.

May 19, 2022: As agreed, Shenkman, on behalf of SVREP, files a CVRA complaint against Albany.

18 Aug, 2022: As agreed, Shenkman, on behalf of SVREP, files the stipulated judgement. (I'm not sure why there was such a long delay. Apparently there were some wording disagreements between the City Attorney and Shenkman.

Nov 08, 2022: Albany holds an election for two City Council seats. Albany elects both a Latino and an Asian-American. These are the first Latino and first Asian-American ever elected to the Albany City Council. The "meet and confer" session is not held because it is obvious that PRCV remedied the CVRA allegations, but the City does send $10K to SVREP for Shenkman anyway.